Do you sometimes doubt your decisions? We’ve all, at some point, faced a decision that made us wonder if we were making the right call. Maybe it was related to choosing a study program or taking a particular job. Thankfully, we can improve our decision-making if we understand our natural thinking habits and how they can cause us to make mistakes, says The Art of Thinking Clearly, author Rolf Dobelli. In this The Art of Thinking Clearly summary and review, we look at the 99 common thinking mistakes that Dobelli suggests people often make. As a book summary service, we share who would find this book helpful and give you a review on whether the book is worth reading.

In essence, this article will cover:

- The Art of Thinking Clearly Summary

- The Art of Thinking Clearly Book Review

- Who Should Read The Art of Thinking Clearly

- Other Recommended Sources

- Chapter Index

- About Rolf Dobelli

- The Art of Thinking Clearly Quotes

Let’s dive straight into it!

The Art of Thinking Clearly Summary

According to a 2025 report by McKinsey & Company, our biases almost always get in the way when we have to make a decision. The Art of Thinking Clearly helps readers recognize the common cognitive errors we all make and how they negatively impact our judgment. Author Rolf Dobelli originally compiled a list of these cognitive biases for himself after becoming wealthy and fearing he might lose it all. What started as a personal project soon caught the attention of intellectuals, who encouraged him to publish it.

Dobelli explains that the ideas in this book aren’t a magic cure for all your decision-making problems, but they can serve as insurance against some of the unhappiness we create for ourselves.

Let’s look into some of the main lessons from The Art of Thinking Clearly.

What are the lessons from The Art of Thinking Clearly?

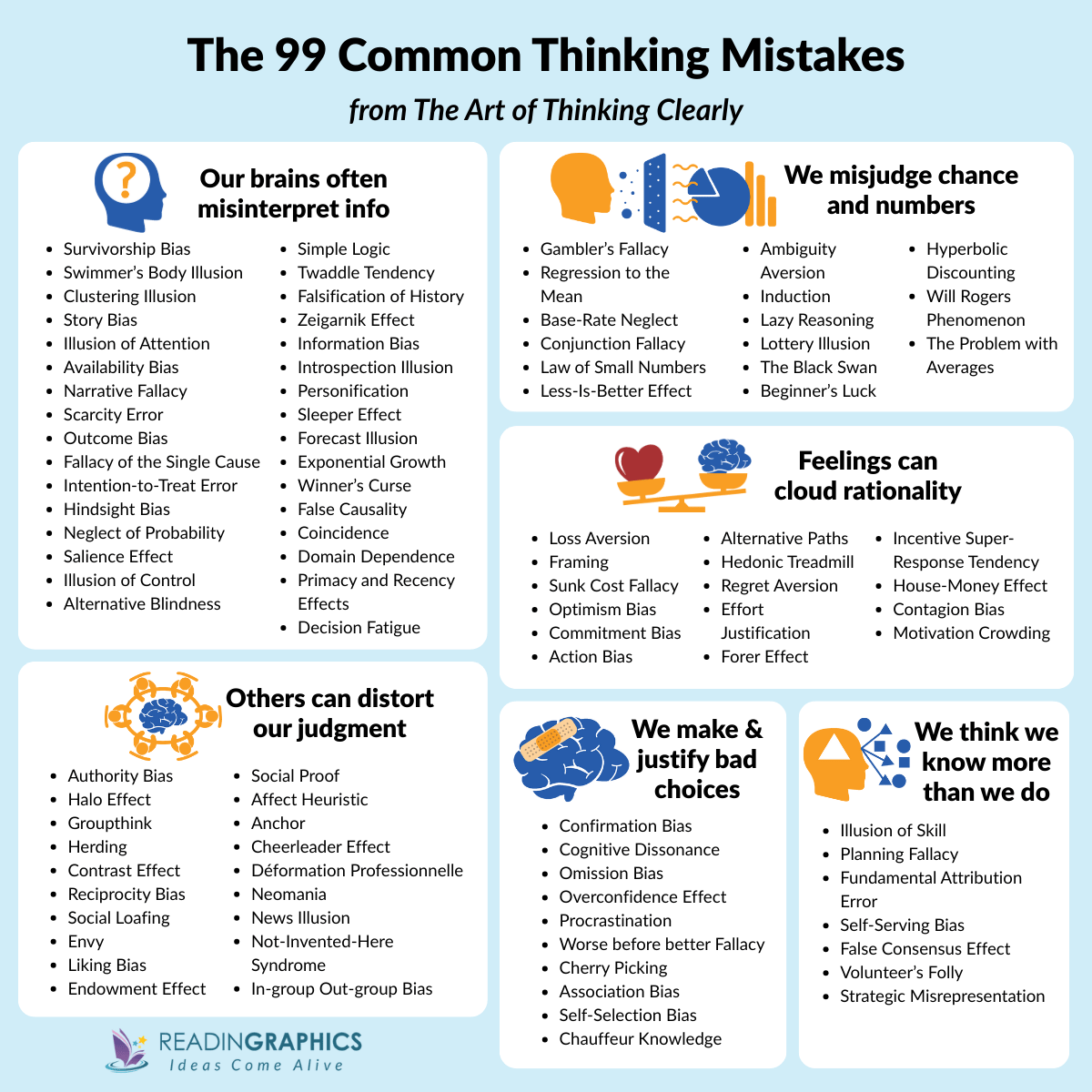

In The Art of Thinking Clearly, Rolf Dobelli reveals how our thinking is full of predictable errors. Our brains often misinterpret information; social pressures and the influence of others can distort our judgment, and our poor grasp of chance and numbers leads us to miscalculate risks and probabilities. The book also explores how emotions and our tendency to overestimate our abilities further cloud our judgment.

While Dobelli shares 99 ideas, this The Art of Thinking Clearly summary groups them into six themes for a broader understanding, with several of his examples listed under each theme.

OUR BRAINS MISINTERPRET INFORMATION

Our brains constantly misinterpret information. Every day, we get flooded with emails, social media, news, and endless opinions, so our minds take shortcuts, using past experiences and what we’ve seen before, to make sense of it all. For example, you might automatically assume the new guy at work will do badly, or trust a product just because it has good reviews from people like you.

These shortcuts can make us jump to the wrong conclusions. According to Rolf Dobelli, here are some ways our brains misread information.

1. Survivorship Bias. We tend to overestimate our ability to succeed because we see a lot of glamorous stories of other people who have succeeded. Remember, the media doesn’t publish stories of failure. If we do the digging, we’ll find out there are just as many, if not more failures, then there are wins. While this is a sad reality, it’s a rude awakening that only a few succeed and many don’t make it to the top.

2. Swimmer’s Body Illusion. We may assume someone looks a certain way because of what they do, for example, a swimmer looks physically good because of their sport. When really they chose that activity because of how they naturally are.

3. Clustering Illusion. Once we figure out a pattern, we think it will remain that way. We must challenge our ideas of patterns and assume that they change.

4. Story Bias. We believe the stories we are told, without questioning the parts that have been omitted.

5. Illusion of Attention. We think we notice everything important around us, but in reality, we overlook a lot because our attention is limited.

6. Availability Bias. We create a picture of the world based on things that we see quite frequently. For example, you may think sugary treats aren’t so bad because your grandmother ate them and nothing happened to her.

7. Narrative Fallacy. We create stories to make sense of random events, even when the story isn’t true.

8. Scarcity Error. We value something more just because it’s rare or hard to get.

9. Outcome Bias. We tend to make judgments based on a result. However, a bad outcome doesn’t necessarily mean the decision was bad. While a good outcome could’ve happened purely because of luck.

10. Fallacy of the Single Cause. We often think an outcome is due to one single cause.

11.Intention-to-Treat Error. We judge a decision based on intentions rather than outcomes.

12. Hindsight Bias. We believe we are better predictors than we truly are.

13. Neglect of Probability. We fail to consider the actual likelihood of events when making decisions.

14. Salience Effect. We pay too much attention to striking or dramatic details and ignore the less visible but important ones.

15. Illusion of Control. We overestimate our ability to influence the things around us.

16. Alternative Blindness. We focus only on the available choices and ignore better alternatives

17. Simple Logic. We prefer simple explanations over complicated stuff.

18. Twaddle Tendency. We think that complicated language means intelligence.

19. Falsification of History. We tend to rewrite the past to make events seem more predictable than they were.

20. Zeigarnik Effect. Unfinished tasks to stay in our minds longer than completed ones

21. Information Bias. We sometimes look for extra information, even if it won’t affect what we decide.

22. Introspection Illusion. We tend to trust our own thoughts about ourselves more than outside evidence, even though we might misjudge our true motives.

23. Personification. We sometimes give human qualities to things that aren’t human, which makes them seem like they act on purpose.

24. Sleeper Effect. Messages from sources we once dismissed can influence us over time as we forget the source.

25. Forecast Illusion. We overestimate our ability to predict the future.

26. Exponential Growth. We underestimate how quickly things grow when they follow an exponential pattern.

27. Winner’s Curse. Winning a bid can lead to overpaying and ending up worse off.

28. False Causality. We tend to mix up correlation and causation.

29. Coincidence. We think unlikely events are causal when they are probably more random than we think.

30. Domain Dependence. We fail to apply knowledge learned in one domain to another.

31. Primacy and Recency Effects. We tend to remember things that happen first and that happen last.

32. Decision Fatigue. The quality of decisions declines after a long session of decision-making.

PEOPLE AND GROUPS DISTORT OUR JUDGMENT.

When we look at what other people do, we might want to shift our behaviour to match theirs. For example, we might see our coworkers take an approach for a project that isnt quite right, but because the whole group seems to be on board, we jump into it.

In addition to attempting to match others’ behaviour, here are several different ways that social dynamics can distort logical thinking and decision-making:

33. Authority Bias. We tend not to challenge authority because we assume they have all the answers.

34. Halo Effect. When one aspect intrigues us, then we tend to think the entire picture will intrigue us. Think about your favourite celebrity advertising a car. You’ll probably like the car, because you like the celebrity.

35. Groupthink. Similar to social proof, we tend to agree to things because we see others do the same.

36. Herding. We follow what others are doing, assuming the majority must be right.

37. Contrast Effect. We judge something to be more spectacular than what it actually is if something is boring next to it.

38. Reciprocity Bias. We tend to do good for others if they do good for us. Think of a salesperson offering a freebie, then requesting you to buy something – you probably would because of the initial good gesture.

39. Social Loafing. When we work in a group, we don’t put as much effort as we would individually.

40. Envy. We compare ourselves to others and feel unhappy when they have what we want.

41. Liking Bias. If we think that people like us, we are likely to do more for them.

42. Endowment Effect. We think that things are more valuable the moment we own them.

43. Social Proof. We think we are behaving correctly when we behave in the same way as others do.

44. Affect Heuristic. We let our emotions toward a person or situation influence our judgment instead of using facts.

45. Anchor. We tend to base our decisions too much on the first information we hear.

46. Cheerleader Effect. People seem more attractive when seen in a group than when seen alone.

47. Déformation Professionnelle. People often see the world mainly through the perspective of their own job or area of expertise.

48. Neomania. We have an irrational preference for new things or innovations simply because they are new.

49. News Illusion. We believe the news provides a true and complete picture of the world.

50. Not-Invented-Here Syndrome. We reject ideas, products, or solutions that were not created by ourselves or our group.

51. In-group Out-group bias. Our natural tendency is to favor members of our own group and distrust others.

WE DON’T THINK LOGICALLY ABOUT CHANCE AND NUMBERS.

We struggle with chance and numbers because our brains were built for survival, not stats. Additionally, we often take mental shortcuts to make faster decisions. Again, this disrupts the accuracy of what we think will happen. That’s why we buy lottery tickets thinking we might win, fear flying more than driving, or assume a stock that’s been rising will keep going. Here are more specific ways we fail when thinking about logic and chance.

52. Gambler’s Fallacy. Humans tend to think the odds change based on what just happened.

53. Regression to the Mean. Extreme results often balance out over time. For example, if a student scores really high on one test, they’ll likely score lower on the next one, not because they got worse, but because results naturally pull toward the average.

54. Neglect of Probability. We worry about things that are unlikely and ignore what’s likely.

55. Base-Rate Neglect. We ignore general facts and focus on the details of a story.

56. Conjunction Fallacy. We think two things together are more likely than one thing alone. For example, “Linda is a bank teller and active in the feminist movement” sounds more believable than “Linda is a bank teller.”

57. Law of Small Number. We trust small samples too much.

58. Less-Is-Better Effect. We irrationally prefer a smaller option if it seems more impressive, like choosing 7 good chocolates over 10 mixed ones.

59. Ambiguity Aversion. We’d rather deal with risks we know about than take a chance on something unknown.

60. Induction. We spot a pattern a couple of times and instantly think it’s always true.

61. Lazy Reasoning. We accept the easiest explanation without questioning anything.

62. Lottery Illusion. We overestimate the chances of winning a lottery.

63. The Black Swan. We are bad at predicting major events with a massive impact.

64. Beginner’s Luck. We create a false link between the first try and achieving success.

65. Hyperbolic Discounting. We prefer smaller, immediate rewards over larger, delayed ones.

66. Will Rogers Phenomenon. Moving something from one group to another can make both groups’ averages look better, even though nothing really changed.

67. The Problem with Averages. Averages hide the real picture.

FEELINGS CLOUD RATIONALITY.

Our feelings and emotions are tied to our survival instincts, says executive coach Moshe Ratson. In many cases, they direct how we respond to situations. For example, you’re paired with a colleague that you don’t like. They offer great suggestions, but you ignore them as your negative feelings towards them outweigh their contribution. This is just one illustration of how emotions can influence us; Rolf Dobelli offers further examples of ways in which feelings can cloud our rationality.

68. Loss Aversion. We hate losing more than we love winning. If we lose $100, we feel worse than if we gain $100.

69. Framing. The way something is presented changes how we feel about it. For example, “90% survival rate” sounds better than “10% mortality rate,

70. Sunk Cost Fallacy. We stick with something just because we’ve already invested time, money, or effort.

71. Optimism Bias. We expect things to turn out better than they actually do

72. Commitment Bias. Once we make a choice, we stick with it, even if it no longer makes sense.

73. Action Bias. We feel the need to act, even when doing nothing is better.

74. Alternative paths. We underestimate risk because we hardly consider all possible outcomes.

75. Hedonic Treadmill. After moments of great happiness or sadness, we return to stable emotions.

76. Regret Aversion. We avoid making decisions that might lead to regret.

77. Effort Justification. We convince ourselves that something was worth it just because we worked hard on it, so we do not feel uncomfortable about the effort.

78. Forer Effect. We believe that broad personality descriptions are accurate.

79. Incentive Super-Response Tendency. We overreact to incentives and distort behavior to chase rewards.

80. House-money Effect. We treat money that we win or inherit more frivolously than money that we earn from our own efforts.

81. Contagion Bias. We believe objects or people can transfer their characteristics through contact.

82. Motivation Crowding. Paying someone to do something they love can make them stop loving it.

WE MAKE POOR CHOICES AND JUSTIFY THEM.

When we do something wrong, we like to justify it. Even if we have to lie to cover up our. It’s often because we can’t stand the nagging guilt mistake, says authors Carol Tavris and Elliot Aronson. In The Art of Thinking Clearly, Rolf Dobelli provides us with more specific examples.

83. Confirmation Bias. We seek and believe information that supports what we already think.

84. Cognitive Dissonance. We tend to want to justify our wrongs or misjudgements just so we don’t have to admit that we are wrong.

85. Omission Bias. We judge harmful actions as worse than equally harmful inactions.

86. Overconfidence Effect. We overestimate the accuracy of our knowledge and decisions.

87. Procrastination. We tend to delay tasks unnecessarily, even when it causes harm or stress.

88. It’ll get Worse Before it Gets Better Fallacy. We assume that after progress, we experience decline – and then things get better.

89. Cherry Picking. People focus only on the evidence that supports their belief.

90. Association Bias. We link unrelated things, like expensive suits to a man being successful.

91. Self-Selection Bias. When people choose themselves to join a group, the results are skewed.

92. Chauffeur Knowledge. We pretend to understand something you actually don’t.

WE THINK WE KNOW MORE THAN WE DO.

Dobelli argues that we tend to believe we know more than we actually do. Here are several ways how;

93. Illusion of Skill. We think we understand more than we actually do about a topic.

94. Planning Fallacy. We underestimate how much time or resources a task will take.

95. Fundamental Attribution Error. We blame people’s character for their behavior.

96. Self-Serving Bias. We believe we contribute to good things or the well-being of others more than we actually do.

97. False Consensus Effect. We overestimate how much other people agree with our beliefs.

98. Volunteer’s Folly. We overestimate the benefit of volunteering for tasks that provide little real value or impact.

99. Strategic Misrepresentation. We tend to intentionally misrepresent facts.

The Art of Thinking Clearly Book Review

The Art of Thinking Clearly is a helpful guide for anyone looking to overcome thinking errors and make better decisions.

The author covers 99 thinking errors, far more than similar books like Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman or Predictably Irrational by Dan Ariely. Each thinking error is explained with several examples, making the concepts easy to understand and the lessons relatable.

The book is easy to read, with many readers appreciating that each chapter is no more than three pages. This allows for a quick and clear understanding of our common thinking pitfalls.

Criticisms of The Art of Thinking Clearly

There are many repetitions, and several ideas could have been grouped together. This can make the reader feel overwhelmed at times.

Some readers also find certain ideas contradictory. While Dobelli provides a reference list, he doesn’t include anecdotes, which makes it harder to see the reasons for his claims about how our brains work.

Despite these drawbacks, The Art of Thinking Clearly is an excellent start for people wanting to learn more about cognitive biases. Furthermore, for those with basic knowledge on how the brains work, it’s a great reminder of our cognitive biases.

Comparison with Thinking, Fast and Slow

In Thinking, Fast and Slow, the science and theoretical framework are very clear. Kahneman’s approach is more research-driven and grounded in psychology, while Dobelli’s book focuses on simplicity and practical application.

The Art of Thinking Clearly rates 4.5 on Amazon (7361 reviews), and 3.8 (39 599 reviews) on Goodreads.

Who Should Read The Art of Thinking Clearly

If you want to figure out how your mind works, dodge common thinking pitfalls, and make better decisions, at work, in relationships, or just day-to-day, this book is for you.

The Art of Thinking Clearly breaks down thinking errors in a super relatable way, so you can avoid making odd choices.

Other Recommended Sources

Here are some more great reads if you found The Art of Thinking Clearly valuable.

- Nudge by Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein looks at how the way choices are shown to us can affect the decisions we make. It also gives useful tips from behavioral science to help people make better choices in daily life and in government.

- The Chimp Paradox by Steve Peters introduces the concept of the “chimp mind” to explain emotional and irrational reactions. It provides a practical model for managing emotions and improving self-control.

- Thinking, Fast and Slow by Daniel Kahneman explains the two systems of thinking – fast, intuitive thinking and slow, deliberate thinking. It goes deeper into the science and offers a strong theoretical framework, helping readers better understand how the brain works, and avoid snap judgements.

Subscribe to access these along with 300+ best-selling book summaries, to begin your own journey to personal and professional growth!

Or, you can purchase the book here.

Chapter Index

Our summaries are reworded and reorganized for clarity and conciseness. Here’s the full chapter listing from The Art of Thinking Clearly by Rolf Dobelli, to give an overview of the original content structure in the book.

See All Chapters (Click to expand)

Introduction

1: Why You Should Visit Cemeteries: Survivorship Bias

2: Does Harvard Make You Smarter?: Swimmer’s Body Illusion

3: Why You See Shapes in the Clouds: Clustering Illusion

4: If Fifty Million People Say Something Foolish, It Is Still Foolish: Social Proof

5: Why You Should Forget the Past: Sunk Cost Fallacy

6: Don’t Accept Free Drinks: Reciprocity

7: Beware the “Special Case”: Confirmation Bias (Part 1)

8: Murder Your Darlings: Confirmation Bias (Part 2)

9: Don’t Bow to Authority: Authority Bias

10: Leave Your Supermodel Friends at Home: Contrast Effect

11: Why We Prefer a Wrong Map to None at All: Availability Bias

12: Why “No Pain, No Gain” Should Set Alarm Bells Ringing: The It’ll-Get-Worse-Before-It-GetsBetter

Fallacy

13: Even True Stories Are Fairy Tales: Story Bias

14: Why You Should Keep a Diary: Hindsight Bias

15: Why You Systematically Overestimate Your Knowledge and Abilities: Overconfidence Effect

16: Don’t Take News Anchors Seriously: Chauffeur Knowledge

17: You Control Less Than You Think: Illusion of Control

18: Never Pay Your Lawyer by the Hour: Incentive Super-Response Tendency

19: The Dubious Efficacy of Doctors, Consultants, and Psychotherapists: Regression to Mean

20: Never Judge a Decision by Its Outcome: Outcome Bias

21: Less Is More: Paradox of Choice

22: You Like Me, You Really, Really Like Me: Liking Bias

23: Don’t Cling to Things: Endowment Effect

24: The Inevitability of Unlikely Events: Coincidence

25: The Calamity of Conformity: Groupthink

26: Why You’ll Soon Be Playing Mega Trillions: Neglect of Probability

27: Why the Last Cookie in the Jar Makes Your Mouth Water: Scarcity Error

28: When You Hear Hoofbeats, Don’t Expect a Zebra: Base-Rate Neglect

29: Why the “Balancing Force of the Universe” Is Baloney: Gambler’s Fallacy

30: Why the Wheel of Fortune Makes Our Heads Spin: The Anchor

31: How to Relieve People of Their Millions: Induction

32: Why Evil Is More Striking Than Good: Loss Aversion

33: Why Teams Are Lazy: Social Loafing

34: Stumped by a Sheet of Paper: Exponential Growth

35: Curb Your Enthusiasm: Winner’s Curse

36: Never Ask a Writer If the Novel Is Autobiographical: Fundamental Attribution Error

37: Why You Shouldn’t Believe in the Stork: False Causality

38: Why Attractive People Climb the Career Ladder More Quickly: Halo Effect

39: Congratulations! You’ve Won Russian Roulette: Alternative Paths

40: False Prophets: Forecast Illusion

41: The Deception of Specific Cases: Conjunction Fallacy

42: It’s Not What You Say, but How You Say It: Framing

43: Why Watching and Waiting Is Torture: Action Bias

44: Why You Are Either the Solution—or the Problem: Omission Bias

45: Don’t Blame Me: Self-Serving Bias

46: Be Careful What You Wish For: Hedonic Treadmill

47: Do Not Marvel at Your Existence: Self-Selection Bias

48: Why Experience Can Damage Your Judgment: Association Bias

49: Be Wary When Things Get Off to a Great Start: Beginner’s Luck

50: Sweet Little Lies: Cognitive Dissonance

51: Live Each Day as If It Were Your Last—but Only on Sundays: Hyperbolic Discounting

52: Any Lame Excuse: “Because” Justification

53: Decide Better—Decide Less: Decision Fatigue

54: Would You Wear Hitler’s Sweater?: Contagion Bias

55: Why There Is No Such Thing as an Average War: The Problem with Averages

56: How Bonuses Destroy Motivation: Motivation Crowding

57: If You Have Nothing to Say, Say Nothing: Twaddle Tendency

58: How to Increase the Average IQ of Two States: Will Rogers Phenomenon

59: If You Have an Enemy, Give Him Information: Information Bias

60: Hurts So Good: Effort Justification

61: Why Small Things Loom Large: The Law of Small Numbers

62: Handle with Care: Expectations

63: Speed Traps Ahead!: Simple Logic

64: How to Expose a Charlatan: Forer Effect

65: Volunteer Work Is for the Birds: Volunteer’s Folly

66: Why You Are a Slave to Your Emotions: Affect Heuristic

67: Be Your Own Heretic: Introspection Illusion

68: Why You Should Set Fire to Your Ships: Inability to Close Doors

69: Disregard the Brand New: Neomania

70: Why Propaganda Works: Sleeper Effect

71: Why It’s Never Just a Two-Horse Race: Alternative Blindness

72: Why We Take Aim at Young Guns: Social Comparison Bias

73: Why First Impressions Are Deceiving: Primacy and Recency Effects

74: Why You Can’t Beat Homemade: Not-Invented-Here Syndrome

75: How to Profit from the Implausible: The Black Swan

76: Knowledge Is Nontransferable: Domain Dependence

77: The Myth of Like-Mindedness: False-Consensus Effect

78: You Were Right All Along: Falsification of History

79: Why You Identify with Your Football Team: In-Group Out-Group Bias

80: The Difference between Risk and Uncertainty: Ambiguity Aversion

81: Why You Go with the Status Quo: Default Effect

82: Why “Last Chances” Make Us Panic: Fear of Regret

83: How Eye-Catching Details Render Us Blind: Salience Effect

84: Why Money Is Not Naked: House-Money Effect

85: Why New Year’s Resolutions Don’t Work: Procrastination

86: Build Your Own Castle: Envy

87: Why You Prefer Novels to Statistics: Personification

88: You Have No Idea What You Are Overlooking: Illusion of Attention

89: Hot Air: Strategic Misrepresentation

90: Where’s the Off Switch?: Overthinking

91: Why You Take On Too Much: Planning Fallacy

92: Those Wielding Hammers See Only Nails: Déformation Professionnelle

93: Mission Accomplished: Zeigarnik Effect

94: The Boat Matters More Than the Rowing: Illusion of Skill

95: Why Checklists Deceive You: Feature-Positive Effect

96: Drawing the Bull’s-Eye around the Arrow: Cherry Picking

97: The Stone Age Hunt for Scapegoats: Fallacy of the Single Cause

98: Why Speed Demons Appear to Be Safer Drivers: Intention-to-Treat Error

99: Why You Shouldn’t Read the News: News Illusion

About Rolf Dobelli

The Art of Thinking Clearly was written by Rolf Dobelli, a Swiss author, entrepreneur, and thinker known for his work on cognitive biases and decision-making. With a background in business and philosophy, Dobelli has written several international bestsellers that explore clear thinking and rationality. He is the founder of WORLD.MINDS, a community of leading thinkers, scientists, and business leaders, and is recognized for making complex psychological concepts accessible to everyday readers.

The Art of Thinking Clearly Quotes

“The human brain seeks patterns and rules. In fact, it takes it one step further: If it finds no familiar patterns, it simply invents some.”

“As paradoxical as it sounds: The best way to shield yourself from nasty surprises is to anticipate them.”

“it is much more common that we overestimate our knowledge than that we underestimate it.”

“If 50 million people say something foolish, it is still foolish.”

“If your only tool is a hammer, all your problems will be nails,”

“Verbal expression is the mirror of the mind. Clear thoughts become clear statements, whereas ambiguous ideas transform into vacant ramblings.”